The stresses associated with commuting, whether unproductive time, traffic or arriving at work or home on time,are daily barbs, but are by no means the only costs associated with commuting. Frustration, boredom, drowsiness and physical discomfort can also creep in as cumulative costs.

According to the most recent census the average American spends 26 minutes each way on their commute each day. For the 139 million people currently in the workforce, that collectively totals up to 29.6 billion hours each year, or 3.4 million worker-years per anum. The negative effects of longer commutes have been linked to increased obesity rates, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, back & neck pain, divorce, and depression. For many, having a longer commute can lead to a sense of loneliness and social disassociation. In metropolitan areas, the cost can also mean real money. The website Lifehacker.com has calculated the average base cost of commuting at $170/mile per year. Loaded at an average hourly salary of $25/hour this figure jumps to $795/mile per year. Dual income households can double these numbers.

What would you do with the 9 extra days you’d have each year if you could eliminate your daily commute? I’m guessing you wouldn’t choose to spend it stuck in traffic, listening to oldies music or talk radio, with too much on your mind, and not enough time to get where you’re going…

Still, you can argue that 1) your commute is an effect based on where you choose to live, 2) you are in a vehicle also of your own choosing, and 3) you are fully in control of what roads you take, what music you listen too, and who you choose to talk to.

So what is there really to complain about?

Plenty. Much of the unspoken frustration with commuting comes from the fact that the time it uses isn’t good for much else, and you don’t have a choice – you have to do it everyday.

Over time commuting becomes a fixed mindset task for most people, impossible to view in a positive light. The tendency for drivers to view their vehicle as a transportation appliance is underscored by the fact that commuting is inherently uninteresting at the time scale of months and years.

Redefining the work/home commute as a growth mindset activity will invigorate the user’s appreciation for their time in the car, leading to positive personal & societal outcomes and rejuvenated interest in the car.

Technologies Shaping the Current State of Commuting

In the near term there are factors that are changing the landscape of experience currently possible in commuting. The rise in urbanization works directly against the mechanisms that have created commuter culture. An increasing number of metropolitan area dwellers are choosing to commute via mass transit, although this in some ways just repackages the same frustrations into a different transportation platform. Others in this situation have turned to walking or biking as an alternative. While this may not fit everyone’s needs, this group of people report the highest levels of satisfaction with their daily commute1. I believe that this is largely due to the effect that we propose should be emphasized:it turns the “commute” into an act of intention, with clear benefits to health, cognitive engagement, and socialization.

Ride sharing through Über and Lyft create other alternatives, but represent a different cost/benefit ratio, as the service can become expensive if viewed through the lens of daily commuting. It is safe to say however, that ride sharing is an enabler of walking and biking as it can help eliminate the problems associated with inclement weather and the need to pilot a vehicle quickly in heavy traffic.

The current crop of Automotive UIs have also come a long way in a short time.

The consumer can now access a greater range of media and interaction than at any point previous to this. We can listen to any song ever created, find our way to any point on the globe, and talk to anyone we’ve ever known at any time. Unfortunately these innovations are too easily compared to the same experiences on mobile devices that are globally regarded as the gold standard of connectivity. This comparison is rarely favorable to the automotive industry because mobile devices compete on an entirely different and less restricted set of requirements than the automobile. The degree to which drivers use their phones in lieu of built-in infotainment systems also works against the safety factors carmakers endeavor to build into these systems.

Autonomy Expanding the Equation : Personalized, Enjoyable and Efficient Commuting

The first autonomous vehicles will usher in the next evolution in automotive UI. When it initially arrives in the marketplace it will likely be matched with incremental UI improvements that move the commuting experience in the direction of ideality, but for UI the bigger changes will still be upstream.

Initially, the shift to autonomy will allow the vehicle occupant to make better use of current feature sets. It will be possible to begin to offset some of the frustrations consumers have with infotainment systems, as they will be able to dedicate a greater portion of their attention to their operation.

It will also allow commuters to be more strategic in crafting their commute experience.

Currently most commuters habitually rely on a range of known routes, local knowledge of traffic patterns, and occasional inputs from a navigation app. Autonomy will allow them to begin to explore routes on different terms, like the shortest route possible, routes without construction delays, scenic routes, and those that allow them to accomplish errands on their to-do list.

They’ll also be able to focus on relaxation and using their commute time as a transition period between work and home. Sleep will likely also be a popular option, with the infotainment system supplying both the lullaby and alarm clock. Consumers will also undoubtedly spend more time in-vehicle on their mobile phones, tablets, and laptop computers. While the use of screen mirroring will increase in this period, the degree to which these devices find their way onto the screens in-vehicle will largely be limited by the screen architectures available in the vehicle. Until viewing-optimized screens are available for all occupants, the amount of interactive work and play occurring on the infotainment screen will continue to be limited.

Perhaps more important than these new use modes, autonomous vehicles’increased computing power and the additional attention afforded to UI by the consumer will also allow more variation in UI cognitive models. This is one of the most intractable problems in automotive UI. To understand how a greater variety of available cognitive models will benefit the user, it is useful to compare how the current quasi-universal models fail their interests.

Current automotive UIs are criticized for being too complicated and hard to use, yet these are far from the most complex systems and features that consumers deal with daily. As an example of this in action think for a moment about the junk drawer everyone seems to have in their kitchen. Mostpeople could plausibly make a list from memory of their junk drawer’s contents even though it is a disorganized chaotic mess.

So what drives this criticism?

The difference between complexity and complication….

First, let’s acknowledge that from a cognitive standpoint consumers often are of two contradictory mindsets on the subject of simplicity. Anecdotally nearly everyone will agree that a “simple” interface is better than a “complex” one. However, when simplicity means a loss of features, or the need to nest features behind fold-out panels or popups to achieve the perception of simplicity,the resulting interface conditions are usually poorly received. Feature reduction is also at odds with marketing goals, so as reflexive as the desire for perceived simplicity is, its real world value is often questionable.

So what is going on here? Is it that people only think they like simplicity, or is it that they only actually like simplicity if it doesn’t come at a cost?

To unravel this we must first come to grips with the notion that complexity in and of itself is not a bad thing. We live with many dimensions of our own complexity quite happily every day. Think of the last time you went took a vacation trip. It’s likely that the excitement of the trip carried you through the complexity of scheduling time off, negotiating tasks to be completed in your absence, setting away-messages on work phone(s) and email(s), booking flights and hotels, registering for events, sorting logistics against the priorities of everyone in your party, stopping your mail, arranging care for pets, resetting your home thermostat, packing, arriving early to get through airport security, car rentals, navigating in a strange city, finding food… The complexity of the vacation’s total effort is staggering when you think about it. Yet we happily take it on, because we feel the benefit of the vacation outweighs the complexity of the tasks associated with it… We also tend to favor the choices we make at least in part because we can self-contextualize the results.

Similarly, the problem for automotive UI lies in understanding the difference between complexity and complication – they are not the same thing! What consumers of automotive UIs are complaining about is complication, not complexity.

“Simplicity is a mental state, highly coupled with understanding.”

– Don Norman, Living with Complexity

Complexity is personal. It’s organizing your thoughts around a topic in a way that is unique to you, and adapted to the connections you’ve already made in your mind. A messy desk is complex, but not complicated because you understand why things are present and how they are arranged. Complexity, far from being the opposite of simplicity actually implies deep understanding, and the efficiency that goes along with it. The complexity of your own messy desk is appropriatebecause it fits the cognitive system that created it.

On the other hand, complication is the effect of trying to fit your mental model into a structure that is preconditioned by rules or behaviors other than your own . Organizing someone else’s messy desk is complicated because you don’t understand the value of the items or the way that they are arranged. In this case the complexity is inappropriatebecause you lack the key to understand its structure and unlock its complications.

“What makes something simple or complex? It’s not the number of dials or controls or how many features it has: it is whether the person using the device has a good conceptual model of how it operates.”

– Don Norman, Living with Complexity

Understanding relies on two factors – an underlying logic, and the ability of the user to

adapt to that logic. The failings of the current crop of automotive UI’s largely are failures to create a logic structure that is universal enough to allow all users to adapt to it. To be fair, we are talking about an impossibility here – creating a universal logic structure for almost anything is an impossible task.

One size does not fit all…

In the development of current automotive UIs, energy and time are put into variations and options that provide model-differentiated experiences and nuanced brand expressions, but effort is not put into logic structures that acknowledge the multiplicity of individual perception and cognitive processes.

Some examples:

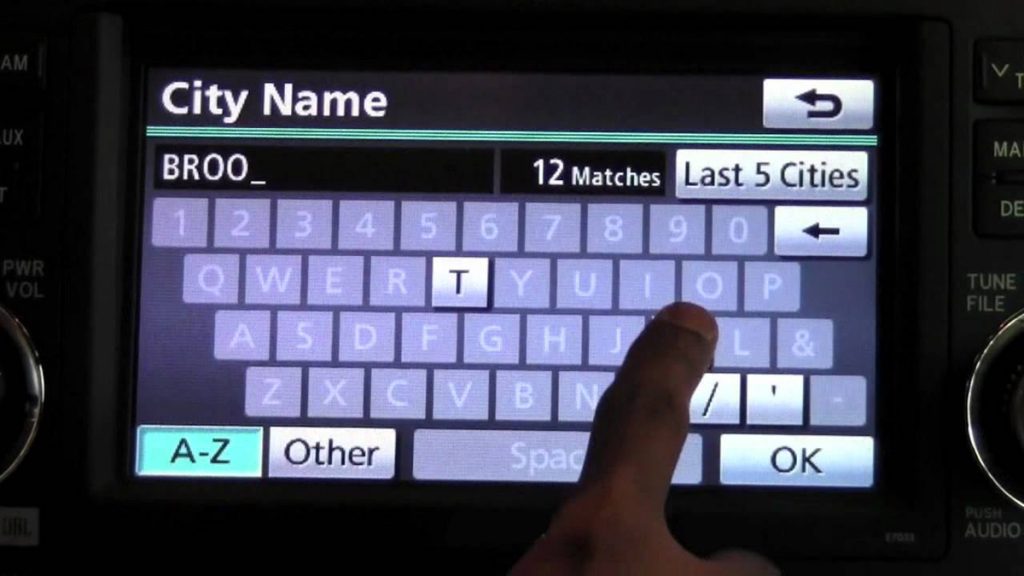

- Nav system destination entry is currently driven by a structural approach that is based on the hierarchal breakdown of the road system. An alternative cognitive model is the dead reckoning approach, which relies on visible landmarks.

- Music libraries also rely on a hierarchal model – genre, composer, artist, album, song. Other cognitive models could be based on common favorites between occupants, play frequency, or historical order.

- Automotive UIs are also the same for all levels of usership – a new user gets the same interface as a veteran user.Alternatively these systems could be merit based. Safe usage behaviors could be rewarded with unlocked features and greater complexity based on the patterns already learned.

To date, one of the most significant constrictions on the proliferation of alternate cognitive models has been hardware and software constraints, both of which are bound by cost, complexity, and integration concerns. Current platforms are designed to fit singular logic solutions, with little room for alternate models and their associated graphic presentations. The need to create “safety-focused” interfaces with limited hardware and processing is the origin of the current one-size-fits-all approach to UI cognitive models.

If this constriction of alternative models is a source of cognitive dissonance, a strong case can be made for it as a false economy. Based on the common perception of automotive UIs as “too complicated” this appears to be supported by consumer opinions.

“Simplicity does not precede complexity, but follows it”

– Alan Perlis

Autonomy Changing the Rules: Growth Mindset Commuting

The real promise of autonomous driving for UI is that it becomes a new interactive space, attractive for its remote but highly connected attachment to both work and home. In this context the vehicle becomes a fourth space, neither home nor work, nor public venue, yet possessing the ability to interact meaningfully with all these spaces. It will maintain the vehicle’s characteristic of being a personal space with useful detachment from the outside world, yet will offer the user a greater range

of experience. This allows the possibility that the nature of the occupant’s commute can shift from serial repetitive drudgery to an active, growth-minded daily exercise.

So, returning those 9 days per year of commuting time to the user might allow them to:

- Follow a pursuit or hobby

- Pursue educational enrichment & learning

- Focus on strategic life goals and personal growth

- Improve their money management

- Mood management

- Relationship enrichment

These activities create opportunities for the OEM to forge new dimensions of their relationship with the vehicle consumer. Using the vehicle can become an ongoing daily relationship with the OEM’s true mobility potential – a portal to experiences beyond point A to point B commuting.

“The notion of the infinite variety of detail and the multiplicity of forms is a pleasing one; in complexity are the fringes of beauty, and in variety are generosity and exuberance.

– Annie Dillard

Strategies : Autonomy will be here soon, start planning for what’s next…

Some strategic areas to consider for the future of automotive UI:

- Automotive domains – definition and ownership

- Strategic Partnerships

- An ongoing daily relationship with the consumer

- Revised Connectivity Strategy

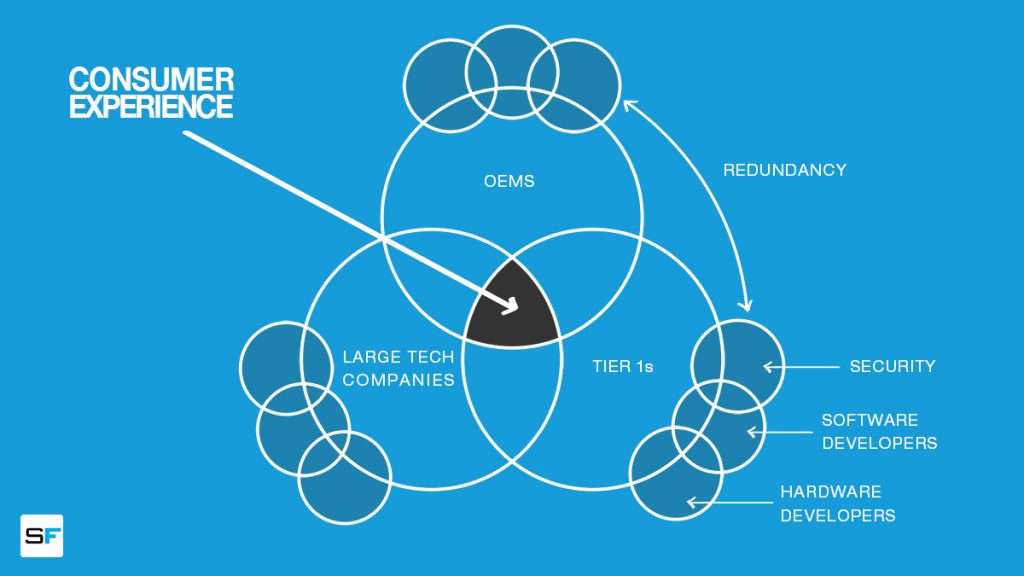

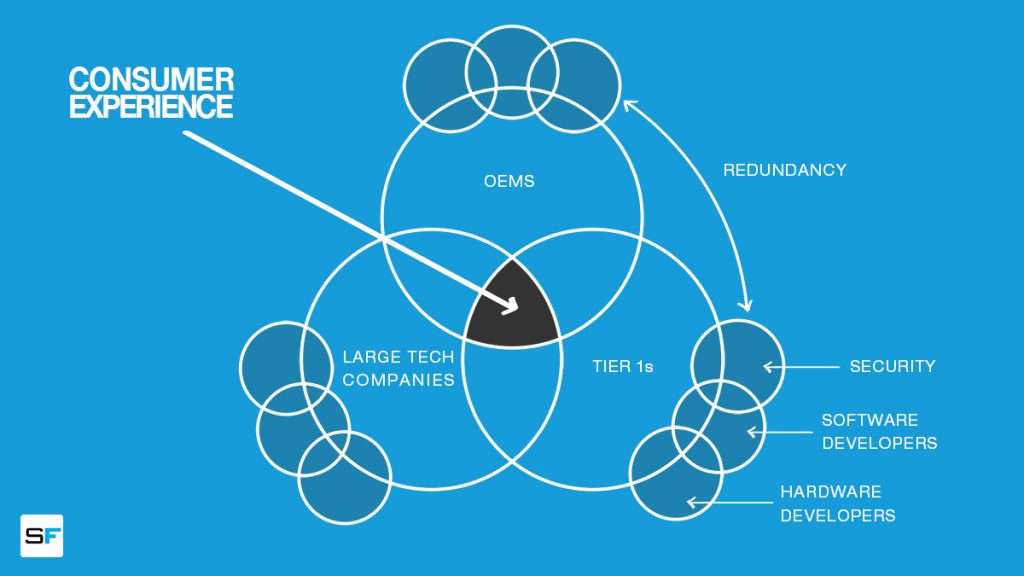

In the tug of war between OEMs and tech companies we must remember to ask what is best for the consumer. There are arguments on both sides of the automotive domain issue that argue for continued ownership of the automotive UI space by OEMs, and equally for greater influence by tech giants like Apple, and Google. The arguments around OEM centered control of the automotive UI space center largely around carving it out as a new “3rdspace” and the desire of the OEMs to dominate that space. Conversely, the tech giants see the automotive UI as a way to garner greater market influence by extending their existing ecosystems. The cohesiveness and focus evident in these ecosystems is appealing to consumers, and difficult (but perhaps worthwhile) for OEMs to emulate. Android Auto (AA) and Apple Carplay are early examples of the tension between OEMs and tech companies. These architectural addenda carve out spaces in the UI where the OEM is forced to accept the dictates of these outside parties. Pointedly, these need to be understood as a wedge intended to open the door for further control if the OEM community fails to assert leadership in this space. Given the predominance of mobile phone UIs it is understandable that the tech companies feel a need to have a presence in automotive UIs. However, as the automotive UI is increasingly the face of OEM branding inside the vehicle, it is debatable whether extending the influence of big tech companies is in the long term best interests of the OEM community. This is not the same as advocating that the automotive industry replicate the capabilities of Silicon Valley. However, it is inconceivable that the opportunities for user engagement afforded by autonomous driving will not drive higher levels of software development in the automotive industry.

Getting back to the idea of complexity-vs-complication one of the chief consumer benefits of Android Auto and Carplay is that they are familiar. Effectively they are able to change the basis of competition by creating contrast between familiar mental models and bespoke OEM solutions.

A cohesive, industry wide strategy for domain control is a crucial concern. Partnerships with application publishers will be an essential component of that strategy, as will the direction of hardware consolidation and development. The drive toward a single domain controller for instrument clusters and infotainment is a crucial first step. Inherent in this is the need for independent software core stability to protect driving critical functions and to realize multi-level software security strategies.

Some attributes of a healthy and growing automotive UI space:

- Consumer driven UI features and attributes

- Cohesive ecosystem benefiting both the OEM community and tech companies

- Vibrant marketplace for all forms of online interaction

- A clean and relatable intersection between driving and online interaction

- Apps talking to apps = Leverage and flexibility

- Absolute consumer faith in the security of the automotive UI space

- A robust system of financial exchange and support based on backend B2B interaction

The good news is that we are still in the growth phase of automotive UI, and win-win scenarios are still a definite possibility.

Wrapping up…

The vitality of the OEM community will be greatly affected by coming developments that will allow a shift of user attention away from driving. Significant opportunities for business growth will be realized by those who can provide contextualized user experiences, and successfully balance UI complexity against complication.

Redefining the commute as a growth mindset activity will allow both OEMs and 3rd party tech companies to rejuvenate the user’s appreciation for their commute leading to positive personal & societal outcomes and invigorate interest in the car.

Sources:

Lifehacker.com

Melanie Pinola, 11/02/11

2. Living With Complexity

Don Norman

MIT Press 2011

ISBN 978-0-262-01486-1

3. Flat UI Elements Attract Less Attention and Cause Uncertainty

NNGroup.com

Nielsen Norman Group

Kate Morgan 9/3/17